The Hotchkiss family not only helped save our institution from extinction, but faithfully demonstrated sacrificial service and wholehearted trust in the Lord.

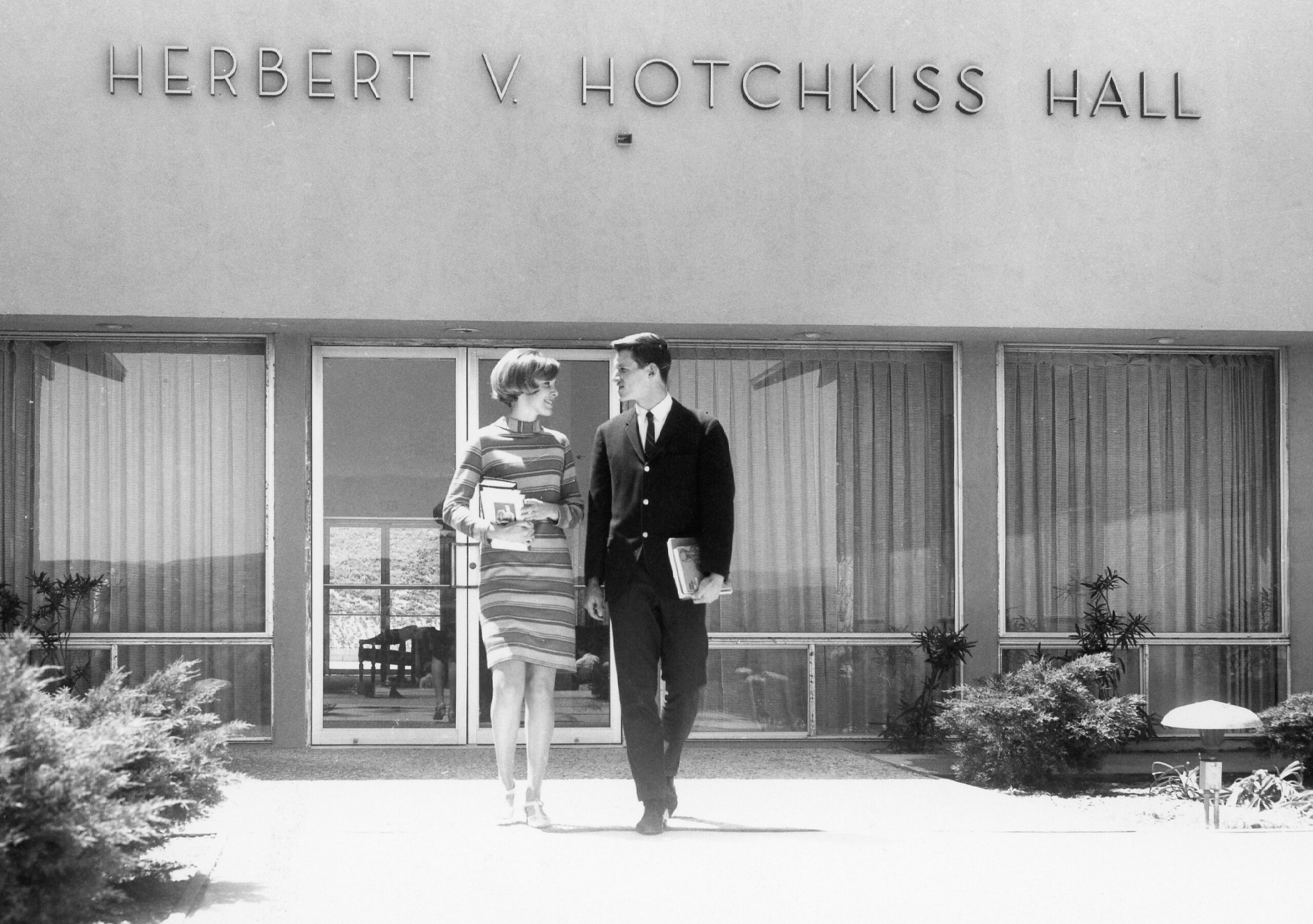

Hotchkiss Hall has housed students, like these two, since 1965. But the Hotchkiss family’s legacy extends far beyond the dorm named in Herbert’s honor.

Editor’s note: The Master’s University (previously Los Angeles Baptist Theological Seminary, Los Angeles Baptist College, and The Master’s College) is nearing its 100th year as an institution. As we approach the milestone in 2027, this is the second in a series of stories about men and women used mightily by the Lord in our history.

When Dr. Herbert Hotchkiss first received the invitation in 1947, he and his wife Marjorie weren’t particularly excited. Los Angeles Baptist Theological Seminary (LABTS) wanted Herbert to leave his home in Philadelphia and the church he had pastored for 17 years to come teach in California.

Decades later, Marjorie recounted the reasons for their hesitation in a written history she drafted for the school.

“First, with all of our families in the East, we had never had a desire to move to the ‘wild and woolly west,’” she wrote in 1991. “Secondly, we were a family of seven, five children whose ages ranged from 13 down to 2, and we had no car and no savings.”

The “no savings” part was critical, because LABTS, then 20 years old, was struggling financially and on the cusp of closing.

“If the school had no resources, how could they afford to bring us west, and support us once we were there?” Marjorie wrote. “No, it was not a sensible move to consider, so my husband wrote that though he was concerned for their survival, he believed the more reasonable direction for the school would be to pursue a man with fewer children, freer and more mobile.”

However, Dr. Carl Sweazy — then a member of LABTS’s board of trustees and the source of Herbert’s life-changing invitation — was insistent. He asked the Hotchkisses to pray about it. They said they would. And as they prayed, their hearts began to shift. Passages in Scripture about trusting the Lord and following where He calls rang loud in their ears.

Then the situation became even more dire. In July 1947, the Hotchkisses learned that the board of LABTS had voted to close the school. The school’s existing leadership had imploded, and resources just weren’t there to continue any longer.

But by then, the Hotchkisses were resolved. They would go, and Herbert would help save the school. He wrote back urging them not to go forward with closing; he was coming, along with another East Coast academic named Dr. Milton Fish, who had also agreed to help.

With LABTS hurting for funds, there was no help to be received with moving expenses and no guarantee of a salary when Herbert got there. But that didn’t matter. The Hotchkisses packed their young family into a 1941 Buick Special bought on a loan from Herbert’s father and drove west, trusting the Lord to provide.

And provide He did — and not just financial means to survive in California, or friendships in a place where they knew no one. In response to that decision to leave their lives behind for an uncertain future, the Lord has provided the Hotchkiss family with an enduring legacy through their ministry to students and the continued existence of a school that probably would not have survived without them.

John Hotchkiss, who ultimately followed in his father’s footsteps and taught for four decades at what became The Master’s University, says Herbert “came as a protector of the vision” of the school.

“I think my parents saw this as God’s way of using them in a ministry that was worth preserving, worth investing in — worth giving their lives to.”

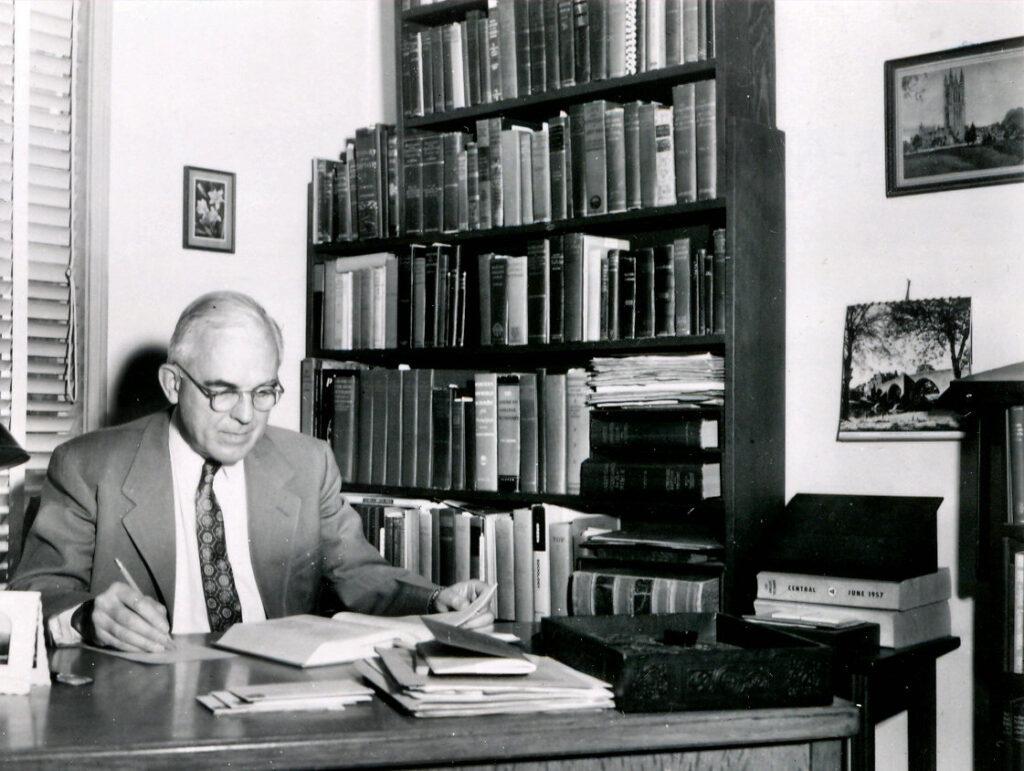

Despite Herbert’s strenuous schedule, LABTS’s 1958 yearbook notes that “his classes always show thorough preparation.”

For Herbert, this wasn’t the first time he’d sacrificed a more comfortable life because he felt called to ministry.

He was once on track for a stable career in academia, teaching English at Cornell University and later Wheaton College. But when he felt a call to pastoral ministry, he switched tracks to study at Westminster Seminary and take up the pastorate at Spruce Street Baptist Church in Philadelphia. Though he taught at Philadelphia School of the Bible on the side, his primary ministry for 17 years was at his church.

Even so, the call to LABTS involved giving up even more security in exchange for a less certain field of ministry. There was no knowing whether the school would survive the year. But with the news of Hotchkiss and Fish coming out to help, the board agreed to reverse the closure and keep trying.

The Hotchkiss family arrived in Los Angeles just in time for the start of classes in the fall of 1947. Herbert showed up ready to teach the small but faithful cohort of 15 students who, like him, had agreed to come even with the school’s future on shaky ground.

LABTS was in a hole of debt to the prior year’s faculty, because there hadn’t been money to pay their salaries. In one of his very first acts after arriving, Herbert participated in a Sept. 1 meeting with his fellow professors about this issue.

In the end, they told the school’s board that LABTS should prioritize all necessary expenses, including paying off debt, over paying faculty salaries. Even if that left nothing to pay them with, they resolved that the school not go any further into the red on their account.

“Many learned the meaning of sacrifice in those beginning days,” Marjorie wrote by way of poignant summary.

“Little Johnny Hotchkiss” grew up to become one of the school’s most beloved professors.

Still, the Lord provided financially for the Hotchkiss family. Days after arriving, Herbert connected with an Armenian congregation in the city looking for an English-speaking preacher. Each Sunday, he drove over to preach at the morning and evening services, and this ministry kept his family fed.

Of course, preaching twice on Sundays, on top of his responsibilities at LABTS, made for a trying schedule.

“Both of us are working harder than we ever worked before,” Herbert wrote in April 1948 in a letter to a prospective student. “I lost so much weight and strength for a while that I had to ask the Lord for new strength to do His work. He heard our prayer, and from that day I gained weight, and strength to sit up and work till 2 a.m., when needed several nights a week. There comes a time when an ‘all-out’ effort is needed in the Lord’s service, and this is it.”

As a key member of a small faculty, Herbert was called on to teach across a wide range of disciplines — something his educational background had prepared him for. Drawing from his studies in both literature and theology, he primarily taught Bible, history, and English courses.

Herbert’s conviction that the liberal arts ought to be studied — and particularly studied from a biblical perspective — was instrumental in bringing him to LABTS, and that conviction shone through clearly in his teaching across every subject.

A 1954 Baptist Bulletin article on LABTS quotes Herbert as saying, “The world looks at the Bible through its books; we look at books through the Bible.”

The school’s 1958 yearbook describes Herbert as a “godly and scholarly example” to his students. And despite his strenuous schedule, the book notes that “his classes always show thorough preparation.”

On top of teaching, Herbert also took on many other responsibilities at the school — from corresponding with prospective students and employees, to serving as the registrar, to helping with summer maintenance work.

Marjorie, too, had her hands full, serving at LABTS on what was called the “Women’s Auxiliary.” “We were the voluntary maintenance department of the school in the early days,” she wrote. This group — made up of female students, wives, and mothers connected to LABTS — took responsibility for maintaining dorm rooms, cooking meals, and hosting fundraising dinners that helped keep the school afloat through its leanest years.

“The first decade was probably the most difficult of the school’s history,” wrote Marjorie, “and I recall my husband saying, ‘There seems to be a crisis every day.’ (But) God had provided something to greatly encourage us from the first day we arrived. On the wall of the Seminary building just outside the Dean’s office was a plaque which read:

God hath not taught us to trust in His name

And thus far hath brought us to put us to shame.”

Wrote Marjorie, “That buoyed our spirits many, many times.”

Slowly but surely, the school’s student body and reputation grew. And when Dr. John Dunkin came on as president in 1959, progress accelerated. His first year, Dunkin reversed the policy of paying faculty salaries last, instead making such payments the first priority.

Then, in 1961, the growing school moved locations from urban Los Angeles to rural Newhall. The Hotchkiss family moved with it.

“Our family was eager to move out of the city,” Marjorie wrote. “ … Before the freeway was out that far, Newhall was still something of a frontier town and cost of housing had not accelerated. God’s timing is perfect. We were able to buy an adequate house built in 1943 just a mile from the college.”

All of the hard work and sacrifice of earlier years was finally starting to bear fruit. The school, which began referring to its college division as Los Angeles Baptist College (LABC) in 1961, saw its enrollment grow semester by semester, with the campus and faculty growing alongside.

After Herbert passed away, Marjorie continued pouring herself into LABC. She managed the bookstore and counseled female students, and in the 1970s she spent six years as the dean of women.

One of the incoming students in those days was John Hotchkiss. Only two years old when his family moved to California, “Dr. Hotchkiss’s little son” was often seen hanging around the school.

In the fall of 1963, he showed up on campus as a student for the first time — the fourth Hotchkiss child to do so. He enrolled as a humanities major, following in the footsteps of his father’s education in English.

John says he quickly “fell in with some pretty adventurous dorm-mates,” gaining a reputation as a prankster. But he was also up to his elbows in the same ministry as his parents: building (in his case, literally) the school.

The new campus in Placerita Canyon had previously served as Happy Jack Ranch, and turning it into a usable learning space, John says, was “an adventure like no other.”

“I just remember that building after building after building went up,” he says.

When the school moved from Los Angeles to Placerita Canyon in Newhall, Herbert and the Hotchkiss family moved along with it.

John helped build many of these with his own hands, both during high school and as an LABC student. “I did framing and masonry work — I drove tractors,” John remembers. He worked on Vider and Rutherford halls, Powell Library, and the “White House” (now the Chancellor’s House).

Then, in 1964, he turned his labors toward a new project: a large H-shaped dormitory with room for 200 students. Along with other classmates, John worked long days on that project at less than a dollar an hour.

The next year, the finished project was dedicated in honor of John’s father, and generations of students have since called Herbert V. Hotchkiss Hall home. John was one of its very first residents.

“The board just gravitated toward naming it after him,” John says. “He didn’t donate money, but he did spend the last 20 years of his life in the preparation of students and the service of the Lord.”

Meanwhile, Herbert’s health was failing. He was already in his 50s when he made the move to California, and the stresses of his responsibilities wore on him. In the same year that Hotchkiss Hall was dedicated, he suffered from severe heart failure. Though he resumed work afterward, he taught only half the number of classes as before.

The years had been hard on Herbert. In fact, John says that his father never adjusted to the West Coast’s climate and culture. “But he never complained, and he never thought of going back,” John says. “He saw this as God’s will. And he loved the students — he just poured his life into preparing them.”

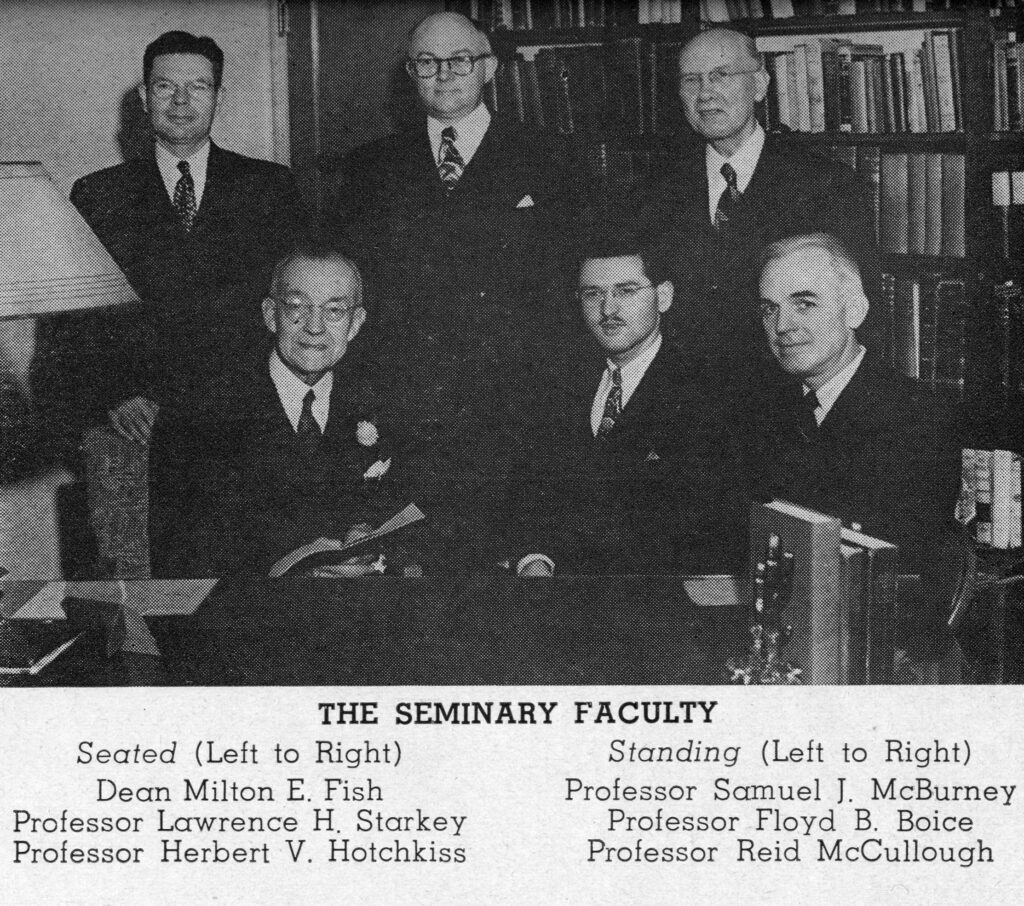

LABTS’s faculty shortly after Herbert arrived in 1947.

Herbert took the duty of teaching the next generation of believers very seriously. In a 1962 document, he used military language to describe the necessity of a Christ-honoring education, writing, “Freshmen in secular colleges are not prepared to meet the attacks on Christian faith. … Green troops are not prepared for battle. They need Christian, battle-wise teachers.”

Herbert kept up the fight nearly to the last moment. In 1968 he taught his final class at LABC, and he entered glory in January 1972, ten days before his 78th birthday.

By then, John had already stepped in as LABC’s Prof. Hotchkiss.

John graduated from LABC in 1967 (marrying his classmate Sharron Roberts the same year) and went on to further studies in English at Pepperdine University.

“The idea was to prepare and get my graduate degree so that I could come back and fill in the gap that Herbert Hotchkiss had left,” John says.

John began teaching at LABC in 1969. “I was only 24,” he says. “But I knew how to read and write and explain things. And I just got better at it as time went on.”

LABC president John Dunkin presents John Hotchkiss with the school’s Alumnus of the Year Award.

Though Herbert was gone, Marjorie was far from done pouring herself into LABC.

In fact, as her house emptied, with her children steadily filtering through LABC, marrying, and starting families of their own, she found herself with more time to serve. She managed the bookstore, counseled female students, and opened her home to those who needed housing. In the 1970s, she even spent six years as the school’s dean of women.

In Carl Sweazy’s written history of the school, he made a special note of Marjorie’s contributions.

“Along with many others, I look upon Mrs. Hotchkiss as the ‘mother’ of our college,” he wrote. “… (T)his exceptionally gifted and personable woman has served the college in many capacities. … I have witnessed her consistent loyalty and love for the school through the years. Her quiet, gracious, dignified service ranks her among the ‘greatest’ on our campus.”

In 1976, LABC granted Marjorie an honorary bachelor’s degree. And though she retired the next year, she wrote that she continued to “have a vital interest in the college through prayer and other support.”

John, meanwhile, faithfully served as an English professor for more than four decades, soon rising to the position of department chair. He taught generations of students and mentored new English faculty as they joined the school, including current professor Dr. Kurt Hild.

“He was every bit a friend as he was a colleague and mentor,” says Hild. “He was so bright and so knowledgeable, and he had such a humble, careful, thoughtful, gentle way of teaching students. I am indebted to him for more than I would ever be able to say.”

All told, John spent 66 years of his life in and around the school that is now The Master’s University.

“For the majority of the school’s history, little Johnny Hotchkiss was hanging around somewhere, doing something,” says John, who now lives in Tennessee with his wife Sharron. “I would never have imagined having a career of almost 45 years in one place. That was the grace of God, and then the grace of the directors to keep putting contracts in front of me.”

John Hotchkiss, left, shares a light moment with Dr. Dunkin, center, after John joined LABC’s faculty.

John retired in 2013. At that year’s commencement ceremony, he was honored by Dr. John MacArthur for his wisdom and kindness as a professor. A news article written at the time records that he received a standing ovation from the students in attendance.

“John (Hotchkiss) played a major role in building out the English major,” says Dr. John Stead, executive vice president of TMU. “And he was probably the best of all of our faculty in his comprehensive concern for preserving the history of the University. He’s contributed substantially to that historical portfolio.”

He did this, in part, by keeping extensive archives of his parents’ documents, which now serve as a window into a crucial period of the institution’s history. Included in these archives is his mother’s firsthand account of those years.

When Marjorie Hotchkiss sat down in 1991, 14 years before her death, to record this perspective on her family’s relationship with LABC, she concluded with these words:

“I praise the Lord that He brought our family to California to be a part of this school which stands so solidly on the Word of God, and continues to train young people for the service of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.”

The Master’s University and Seminary admit students of any race, color, national and ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national and ethnic origin in the administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs.

21726 Placerita Canyon Road

Santa Clarita, CA 91321

1-800-568-6248

© 2025 The Master’s University Privacy Policy Copyright Info

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Notifications