Longtime president helped lay a strong foundation for what The Master’s University is today.

Editor’s note: The Master’s University (previously Los Angeles Baptist Theological Seminary, Los Angeles Baptist College, and The Master’s College) is nearing its 100th year as an institution. As we approach the milestone in 2027, this is the fifth in a series of stories about men and women used mightily by the Lord in our history.

In 1927, Dr. William Matthews founded Los Angeles Baptist Theological Seminary as a place where believers could receive biblically faithful preparation for lives of service to Christ.

For the school’s first 16 years, Matthews guided and protected that vision. When he died, he left behind a school with a clear mission but a desperate need for a leader who would take up the torch.

What followed were difficult years overseen by interim and short-term presidents. Between 1943 and 1959, LABTS saw a series of five different men lead the school. These faithful leaders kept the flame alive, but the school struggled to grow or find financial stability.

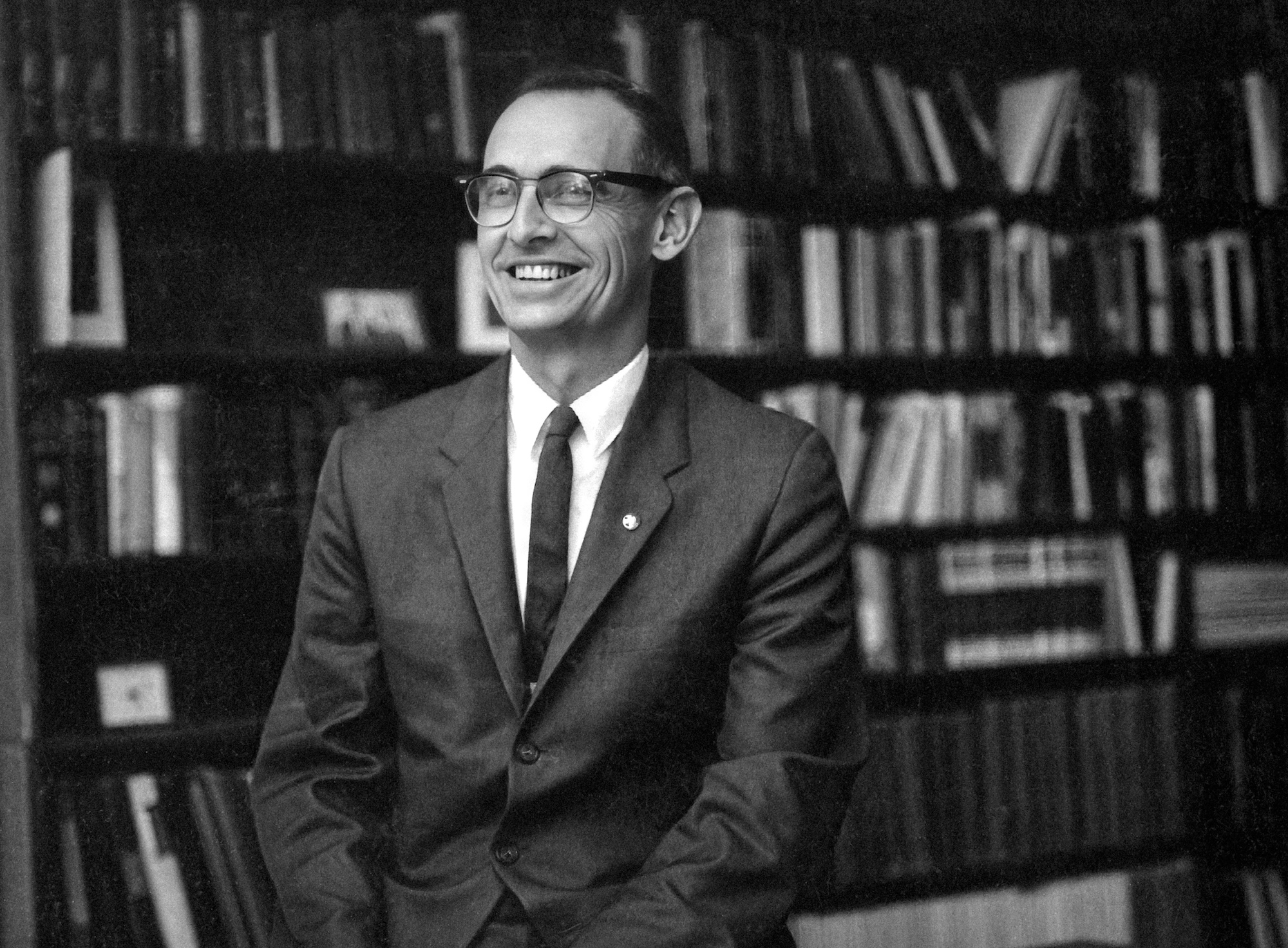

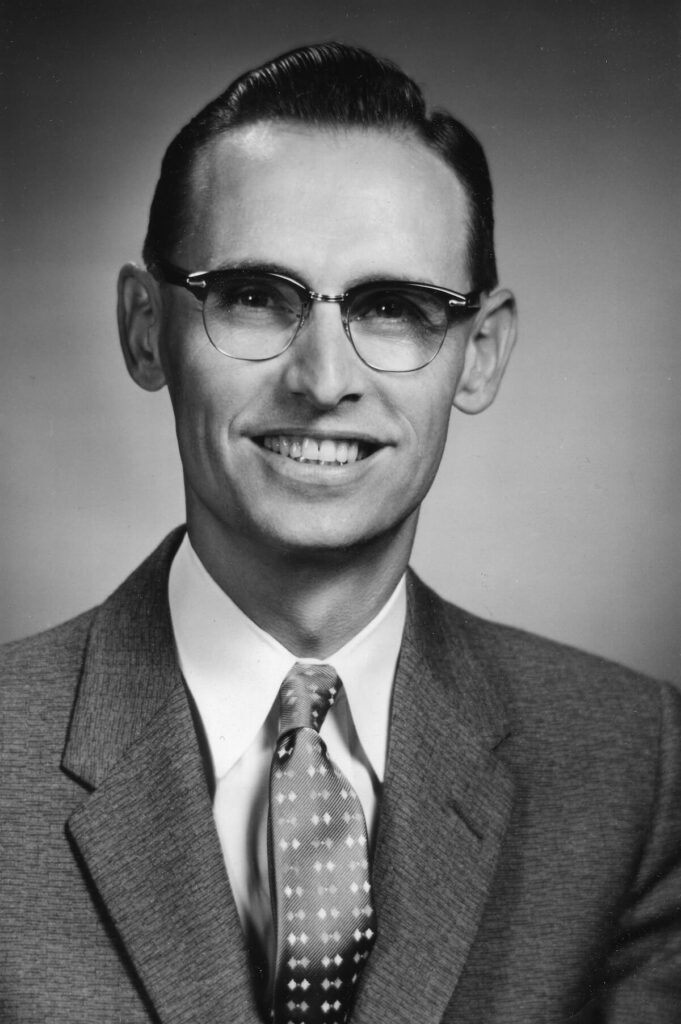

Then in 1959, Dr. John Dunkin answered the call. During his 26 years as president, he oversaw the school’s relocation to Newhall, the construction of many buildings that remain cornerstones of campus today, the flourishing of its liberal arts program, and the securing of regional accreditation. In it all, Dunkin demonstrated unflinching Christian character, and his labors preserved and expanded the school’s original vision, helping lay the foundation for what The Master’s University is today.

Dunkin believed that Christians should have not only a liberal arts education, but a distinctively Christian liberal arts education.

In 1920, seven years before Matthews founded LABTS, John Dunkin was born in the town of Aldershot in Ontario, Canada. His father was wealthy, the owner of a Cadillac agency outside of Toronto. But more than that, Dunkin’s father modeled sincere faith in the Lord and commitment to his family.

When it came time for Dunkin to attend college, his father reportedly told him, “You can go to any school you want; but I’ll pay for it if you go to Wheaton.”

So, he went to Wheaton. There, he gained two things: his bride, Jane, and his deep appreciation for Christian liberal arts education.

“Wheaton was by far the best evangelical Christian liberal arts college at the time,” says Dr. John Stead, executive vice president of TMU and Dunkin’s son-in-law.

After Wheaton, Dunkin went on to Dallas Theological Seminary, where he earned his master’s degree and doctorate. While there, he served as an interim pastor at a nearby church, and the Dunkins began to grow their family, ultimately having a son and five daughters.

Soon, his career veered toward education. Dunkin moved to Johnson City in New York to serve as a dean and instructor at Baptist Bible Seminary. After several years, in 1958, a group of California Baptists contacted him, asking if he would be willing to serve as president of a brand new seminary in Oakland called San Francisco Conservative Baptist Theological Seminary.

He accepted. However, his daughter, Ellen Stead, recalls that Dunkin soon realized that the venture was not a good match for him.

So, when he was approached the following year by a different Baptist seminary in California — none other than LABTS — he embraced the opportunity.

For LABTS, Dunkin was a clear choice for president. Though he came from a nondenominational background, Dunkin found agreement in convictions with the General Association of Regular Baptists (GARB), the conservative Baptist organization affiliated with LABTS. Dunkin quickly became a prominent speaker and scholar within the GARB. More than that, he had a broad education in the liberal arts, a deep background in theology, and lived experience as a school administrator.

He and LABTS also shared the same heart: training Christian young people for lives of service.

On July 30, 1959, he received a call from LABTS’s board chairman. On Aug. 4, he visited the school to meet with the board and faculty. And 10 days later, he received and accepted the offer to become president — a position he would hold for more than a quarter century.

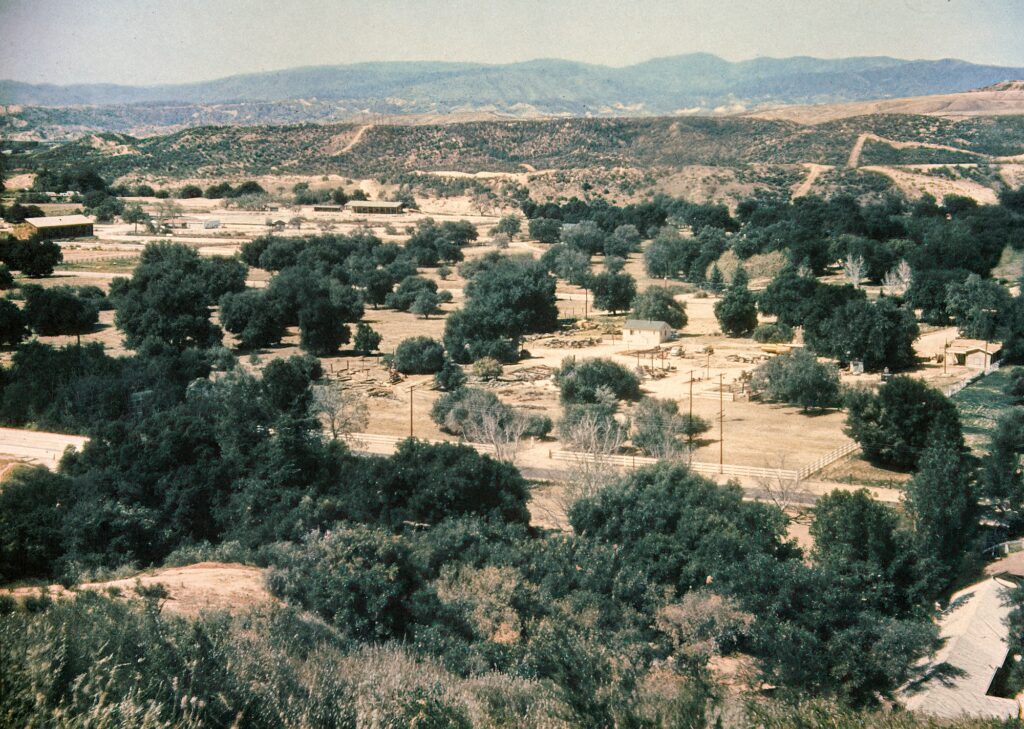

In 1961, LABTS found its new home in Newhall. This photo of Placerita Canyon was taken that same year.

When the 39-year-old John Dunkin arrived in Los Angeles in 1959, he found LABTS trying desperately to survive in a challenging situation. Then located on a tiny half-acre lot at 2117 East Sixth Street, the school was cramped, even with a meager 50 students. It was also tens of thousands of dollars in debt and unable to reliably pay its faculty.

Dunkin immediately went to work. Rallying the board of trustees to cover the cost, he ensured that all salaries were paid at the end of his first payroll cycle.

“Under the previous administrations, the bills were paid first, and the faculty was paid if there was money left over,” says Dr. John Hotchkiss, whose father, Herbert, was a professor at LABTS in 1959. “But when Dr. Dunkin came, that policy was one of the first things he reversed.”

Starting his first month as president, Dunkin launched an aggressive communication and fundraising campaign, mailing monthly LABTS updates to churches in the GARB and other friends of the school, always with requests for donations in order to cover payroll and other expenses. He also took up an exhausting travel schedule, driving to visit and preach at far-flung Baptist churches to drum up support.

After payroll, debt reduction was a top concern for Dunkin. Over the course of his first year, he persuaded donors to help reduce LABTS’s debt from $41,798 to $28,792. But LABTS’s financial situation was far from the only problem to solve. What they needed as much as anything was a new campus.

“Dr. Dunkin was determined that the school would continue,” says John Hotchkiss, who graduated from LABC in 1967 and later taught under Dunkin. “And he was known for saying, ‘We cannot continue and grow the school in this place.’”

The search for a new campus was frustrated by LABTS’s finances. Any affordable properties had unworkable problems. Any usable properties were prohibitively expensive.

But then, in early 1961, they found it. Far up the road on Sierra Highway, tucked away in a rural valley community called Newhall, a 28-acre piece of land was up for sale. Used in part as a ranch-style youth camp called the Happy Jack Ranch, the land had a few old buildings, a hillside topped with a pool, and oak trees sprawling in every direction. Across the street, a flock of sheep grazed. The immediate neighborhood consisted of a few homes and a dairy farm.

The price was steep — $152,500 — but the location was ideal.

Dunkin and the board got to work, and the school held daily prayer meetings for the project. The closing deadline was set for May 5. When the day rolled around, LABTS had raised a total of $19,200 to offer as a down payment. The owners accepted.

“Finding and financing the campus was absolutely huge,” Hotchkiss says. “I don’t think the school would exist if Dr. Dunkin had not been a man of vision and faith.”

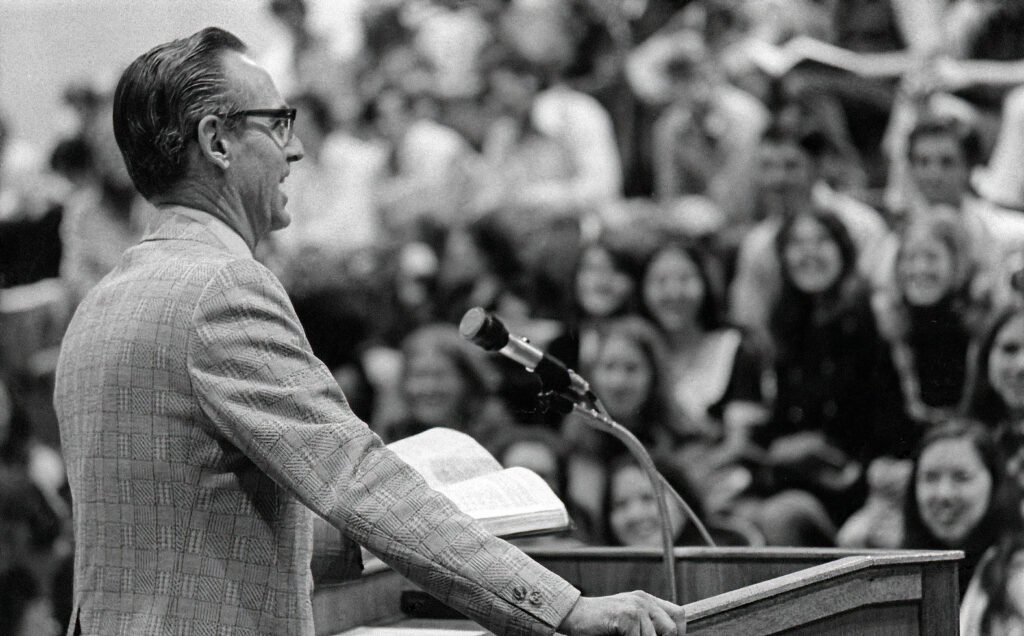

Dunkin was a regular presence behind the pulpit in chapel at LABC.

The widening of LABC’s physical footprint paralleled a simultaneous expansion on a conceptual level.

From the early days of Matthews’ administration, the school had aspired to offer a broad undergraduate education for Christian young people. But a web of interconnected problems — limited facilities, a small faculty, and uncertain finances — had stifled the school’s ability to execute that vision. By the time Dunkin came, the school had largely shrunk back to its initial focus on offering a theological education to aspiring ministry workers.

But Dunkin was committed to the vision of Christian liberal arts education he’d caught at Wheaton. In the first few years after moving to Newhall, the school (by then called Los Angeles Baptist College) added new programs in fields like English, history, music, and science, exponentially increasing the school’s undergraduate offerings alongside the existing graduate seminary program.

“His heart was in ministry and missions,” Hotchkiss says. “But he believed that congregations and pastors and Christian workers should have a broad knowledge base and be familiar with the issues of the day, as well as a grasp of the major events of history.”

In fact, Dunkin believed that Christians should have not only a liberal arts education, but a distinctively Christian liberal arts education.

In an August 1961 note to supporters, Dunkin wrote, “The new birth is indispensable — but it is intended to be nourished (educated, trained, disciplined) and cared for by spiritual guardians, not by strangers to God and to grace. It is our conviction that every young Christian should spend at least two years in a Christian college, if they attend college at all.”

Dunkin aided that goal by broadening LABC’s scope, making the school a better option for a wider variety of students.

The school started its first academic year in Newhall with 71 students and the new, mostly finished Powell Library.

More new buildings went up in quick succession: the “White House” (then a residence for the Dunkins, now the Chancellor’s House) in 1962, Rutherford Hall (an administrative building and dining center) in 1963, Hotchkiss Hall in 1965, and Bross Gymnasium in 1967.

How did they manage to expand so quickly? “Volunteer labor,” Hotchkiss says.

Many plumbers, electricians, and other professionals donated their time. Henry Vider, the namesake of Vider Hall and a prolific local contractor, oversaw many of the building projects as a labor of love. Students, faculty, and staff alike worked on the building sites, mixing cement, laying bricks, and painting walls.

“Dr. Dunkin initiated a prayer circle tradition,” Hotchkiss says. “Once the footings of a building were built, all the students, faculty, and staff would assemble, encircle the foundation footprint, hold hands — if there were enough of us to make it around — and then we would pray, asking for God’s provision for the rest of the building.”

In addition to new buildings and programs, another significant project held Dunkin’s focus through much of his presidency: accreditation.

Throughout the first decades of its history, the school had fulfilled its essential mission without regional accreditation. But as Dunkin leaned into LABC’s liberal arts aspirations, the lack of widely recognized accreditation presented itself more and more as a limitation.

The benefits of seeking and securing regional accreditation were well known to the faculty and trustees: credits from LABC would be transferable to other accredited institutions; alumni would be greatly helped in gaining entrance to a wider range of graduate schools; and donors, parents, and prospective students would be given added confidence in LABC’s academic quality.

In 1964, the school’s board voted to pursue regional accreditation with the Western Association of Schools and Colleges.

The original goal was to complete the process within two years. In the end, it took 11 years of tireless development efforts from Dunkin and others to raise the money needed to meet WASC’s standards, which included a balanced budget and greater educational resources available to students.

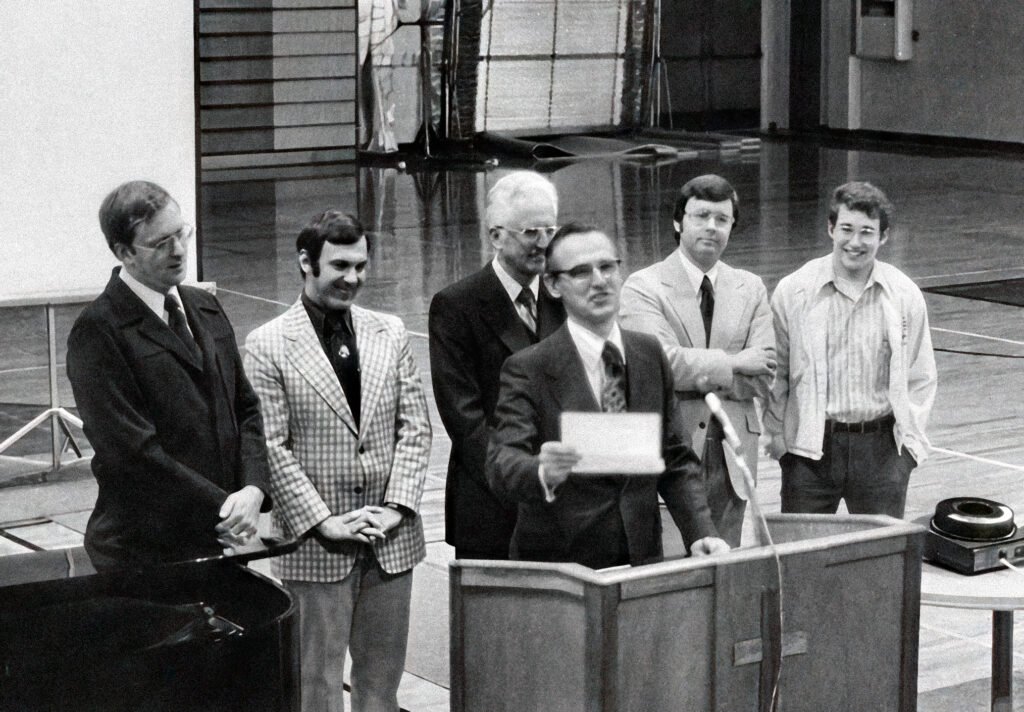

But on March 3, 1975, a letter arrived on Dunkin’s desk minutes before chapel was scheduled to start. He brought it with him to the gym and, in front of the gathered student body, read its message. It was a notice from WASC that LABC had officially received accreditation.

Dr. Gregg Frazer (dean of TMU’s humanities school), who was one of the students in the room that day, remembers the uproarious cheers that broke out.

James Rickard Sr., who served on the board during Dunkin’s administration, says, “Accreditation was one more step forward into solidifying the future of the college.”

And the school’s future was always in need of solidifying — particularly in terms of funding. The treadmill of financial needs had Dunkin almost constantly representing the school on the road and reaching out to prospective donors.

“It was tough, but I never saw him discouraged,” Rickard says. “He was always upbeat and positive. His sweetness and his loyalty to the Lord and to this school helped it through those tough times.”

So did his love for the students. Dunkin loved getting to know them, and he had an excellent memory for their names and stories.

“He did not mind being considered the father figure of what then was a very small student body,” Hotchkiss says. “And so we referred to it as the college family.”

Rickard agrees: “His whole life was LABC. He loved the school. He had a deep, deep love for the Lord, the Lord’s work, and the Lord’s people.”

In 1975, Dunkin stood before LABC’s student body and read the letter from WASC announcing that the school had officially received accreditation.

For the next several years after 1975, LABC saw gradual, healthy growth in enrollment, climbing to nearly 400 students.

Then in the early 80s, a recession hit. The school lost dozens of students in a short span, bringing about familiar financial instability.

Tough times were back. But by then, Dunkin was in his 60s, and his health was beginning to fail. He didn’t have the strength he had decades earlier to do the grinding work of keeping LABC afloat. At the same time, some of his longtime friends on the board were beginning to pass on to glory.

It had been an amazing run. During Dunkin’s presidency, LABC went from offering two undergraduate majors to 14. The school moved to its new home in Newhall, ensuring it had room to grow, and it pushed through the arduous process of securing accreditation. The student body grew from 50 to a peak of nearly 400.

After a fruitful but wearying 26 years, in 1984, Dunkin informed the board that he felt it was time for someone else to shoulder the weight of the presidency.

“At that point in time, we had a major decision to make,” Stead says. “LABC was part of the GARB, which had very little influence on the West Coast in terms of recruiting students. And Dr. Dunkin realized that the school had to get out of that doldrum or it would face financial disaster.”

When a certain nondenominational pastor named Dr. John MacArthur was approached about leading LABC, and responded positively, Dunkin threw the entire weight of his support behind him.

Rickard believes that Dunkin’s support was instrumental in swaying the board — which included a significant number of pastors and laymen in the GARB — to accept a leader from outside the association.

“Dunkin respected MacArthur,” Rickard says. “John MacArthur loves the Word of God. John Dunkin loved the Word of God. They were two peas in the same pod.”

Dunkin’s support of MacArthur cost Dunkin some of his closest friends within the GARB. And when LABC named MacArthur president in 1985, it cost the school its relationship with its longtime association.

“To have the courage to turn it over to Dr. MacArthur, which was not popular in the GARB, took a lot of courage for Dr. Dunkin,” Frazer says. “It hurt him. That act was a personal sacrifice for him, but it caused the school to burgeon and grow and have a greater impact for Christ.”

The same year, the school changed its name to The Master’s College — a name that reflected an important reality: The school was not first and foremost an institution for Baptists, but a school for believers who love the Master and want an education submitted to His lordship.

For his part, Dunkin became the chancellor of TMC and remained very active on campus, enjoying a front-row seat to the tremendous growth that took place under MacArthur’s administration. He continued to raise money for the school using the network he had built, and he maintained friendships with the faculty.

Frazer remembers that Dunkin loved to invite people over for lunch and talk with them about what they were reading.

One time, when they were both attending a party, Dunkin walked up to Frazer on the patio and said, “John (Stead) tells me that you need to be doing a Ph.D. Why aren’t you doing it?”

Frazer replied, “Well, to be honest with you, Dr. Dunkin, I don’t want to saddle my family with tremendous debt.”

“You let me worry about that part of it,” Dunkin said. “You get the process rolling.”

“So I applied, and he arranged for a 90-something-year-old lady in San Luis Obispo to pay for my entire Ph.D. bill,” Frazer says. “I never paid a cent, even for books.”

What would Dr. Dunkin think if he saw TMU today? “He would be singing the Doxology at the top of his voice,” says James Rickard Sr.

One of the last building projects during Dunkin’s presidency was a new student center. It was completed in 1984, and the school elected to name it after the president himself.

“We wanted to honor him with that because he loved the students,” Rickard says. “He was their dad. He was a father to them.”

After he became chancellor, Dunkin’s health continued to decline, a neurological condition leaving him first weak and then wheelchair-bound. His wife, Jane, passed away in 1998, and he followed her in 2005 at the age of 85.

It is easy to appreciate Dunkin for some of his most visible contributions to TMU: helping to secure a new campus and accreditation. But those who knew him say that his most important legacy is one of faithfulness to the Lord and to Scripture.

Frazer says, “I think the biggest part of Dr. Dunkin’s legacy was keeping the faculty and administration tethered very tightly to the Word and to a love for Christ and the church.”

Rickard agrees: “Dr. Dunkin was a true biblicist. He loved the Word of God. He loved the people of God. He loved the college — it was his life. And it came out in so many different ways: the way he spoke, the way he acted, the way he led the chapels. He was LABC.”

What would Dunkin think if he saw TMU today?

“He would be singing the Doxology at the top of his voice,” Rickard says. “He would love every minute of it. He would feel like that’s his legacy being carried on.”

Master’s Connect is the alumni platform for graduates of LABC, TMC, and TMU. Meet other alumni, receive mentorship, view job listings, and more.

The Master’s University and Seminary admit students of any race, color, national and ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national and ethnic origin in the administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs.

© 2025 The Master’s University Privacy Policy Copyright Info

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Notifications